I wrote this post primarily from the perspective of a beginner guitarist trying to solve a practical problem, but the way I approached it naturally landed on functional programming and literate programming. So, you might want to stay around even if you are not interested in playing the guitar. This post is mostly about my experience of learning a very interesting music markup language LilyPond, which has a symbiotic relationship with the GNU Guile Scheme.

Like many beginner guitarists, I have been maintaining a dictionary of guitar chords. In the beginning, I simply drew the diagrams in a notebook, but lately I started to realize that I need a better system to edit them, organize them and rearrangement them… like snippets of code. So I naturally looked into LilyPond. It was like… I could code in Scheme as part of my guitar practice? Where do I sign up?

Chord diagrams

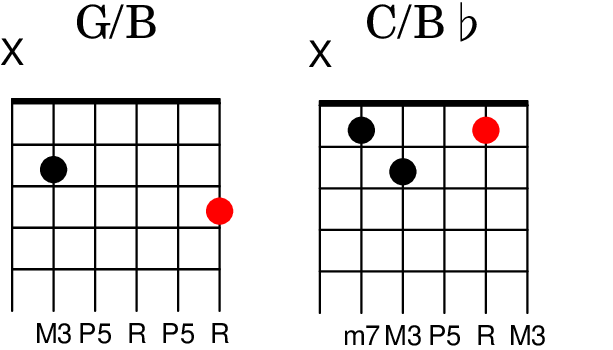

Basically, I want to produce diagrams like this:

The musical aspect about this diagram is not important here, but it is sufficient to say that I want a row of diagrams with a chord name, and a fingering pattern on the fretboard. The root notes are indicated by red dots, and I want the intervals with respect to the root note printed below the fingering diagram. The Lilypond command \fret-diagram-verbose does not have an option for printing intervals, but I hijacked its facility for displaying finger code for my own purpose. Ideally I also want to print the names of the notes below the intervals, but I haven’t figured out a way to do this yet. There are many things that I want to do to make this diagram better, but we’ll stick to the basic at this point.

The most straightforward way to do it in LilyPond is like this:

\markup {

\override #'(fret-diagram-details . ((finger-code . below-string)

(dot-radius . 0.3)

(string-label-font-mag . 0.3)))

\override #'(size . 2)

\center-column {

"G/B"

\fret-diagram-verbose #'(

(mute 6)

(place-fret 5 2 "M3")

(place-fret 4 0 "P5" white)

(place-fret 3 0 "R" white)

(place-fret 2 0 "P5" white)

(place-fret 1 3 "R" red))

}

\hspace #3

\override #'(fret-diagram-details . ((finger-code . below-string)

(dot-radius . 0.3)

(string-label-font-mag . 0.3)))

\override #'(size . 2)

\center-column {

"C/B♭"

\fret-diagram-verbose #'(

(mute 6)

(place-fret 5 1 "m7")

(place-fret 4 2 "M3")

(place-fret 3 0 "P5" white)

(place-fret 2 1 "R" red)

(place-fret 1 0 "M3" white))

}

}It looks very similar to LaTex, but interestingly, we are already mixing Scheme with the markups. The Scheme expressions are indicated by the #. So \override #'(size . 2) means that we are passing a Scheme object to the Scheme function that underlies the markup \override. The recursive nature of lists allows us to use rich data structure in the markups - a feature not found in popular markup languages.

The problem with the code above is that the content (i.e., the fingering patterns) is intermingled with the presentation. Since the content is just Scheme lists, we can separate them from the markups by assigning them to two variables, chordA and chordB:

%%%% The content

chordA = #'(

(mute 6)

(place-fret 5 2 "M3")

(place-fret 4 0 "P5" white)

(place-fret 3 0 "R" white)

(place-fret 2 0 "P5" white)

(place-fret 1 3 "R" red))

chordB = #'(

(mute 6)

(place-fret 5 1 "m7")

(place-fret 4 2 "M3")

(place-fret 3 0 "P5" white)

(place-fret 2 1 "R" red)

(place-fret 1 0 "M3" white))

%%% The presentation

\markup {

\override #'(fret-diagram-details . ((finger-code . below-string)

(dot-radius . 0.3)

(string-label-font-mag . 0.3)))

\override #'(size . 2)

\center-column {

"G/B"

\fret-diagram-verbose \chordA

}

\hspace #3

\override #'(fret-diagram-details . ((finger-code . below-string)

(dot-radius . 0.3)

(string-label-font-mag . 0.3)))

\override #'(size . 2)

\center-column {

"C/B♭"

\fret-diagram-verbose \chordB

}

}The assignment syntax chordA = is the part of the Lilypond markup language, but what follows it is Scheme.

I was still unhappy with the code, because I had to repeat the same sequence of markups twice. We need a macro written in… what else?… Scheme, of course!

%%%% The content, written as Scheme lists

% G/B

chordA = #'(

(mute 6)

(place-fret 5 2 "M3")

(place-fret 4 0 "P5" white)

(place-fret 3 0 "R" white)

(place-fret 2 0 "P5" white)

(place-fret 1 3 "R" red)

)

% C/Bb

chordB = #'(

(mute 6)

(place-fret 5 1 "m7")

(place-fret 4 2 "M3")

(place-fret 3 0 "P5" white)

(place-fret 2 1 "R" red)

(place-fret 1 0 "M3" white)

)

%%%% The macro, written as a mixture of Scheme and LilyPond markup

#(define-markup-command (my-chord layout props chordName chordLst) (markup? scheme?)

"Draw a chord"

(interpret-markup layout props

(markup #:override '(fret-diagram-details . ((finger-code . below-string)

(dot-radius . 0.3)

(string-label-font-mag . 0.3)))

#:override '(size . 2)

#:center-column (

chordName

#:fret-diagram-verbose chordLst

)

#:hspace 3)))

%%%% The presentation, written in the markup language

\markup {

\my-chord "G/B" \chordA

\my-chord "C/B♭" \chordB

}In Scheme mode, we define a Scheme function my-chord, which can be used as a markup \my-chord. Interestingly, although I said that the function my-chord is written in Scheme, the code doesn’t quite follow the Scheme syntax. That is because inside Scheme mode, we use # again to turn into markup mode in Scheme (e.g., #:override '(size . 2) is a markup). I was going to say that the ability to switch from one language to another seamlessly is unique, but then I realized that JSX in web programming uses a similar pattern. But the idea is done more elegantly in LilyPond.

Scale diagrams

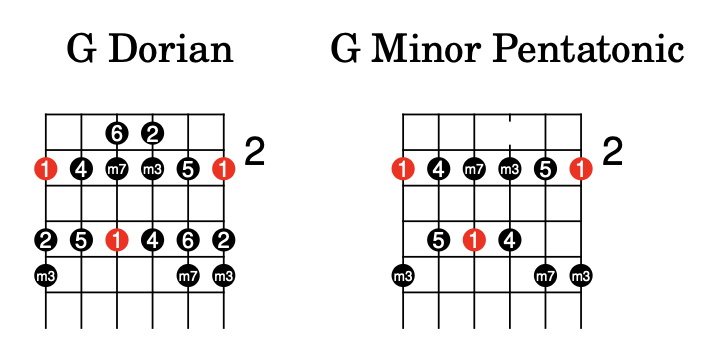

With some minor tweaks (code here), I can also create scale diagrams like this:

LilyPond with org-roam

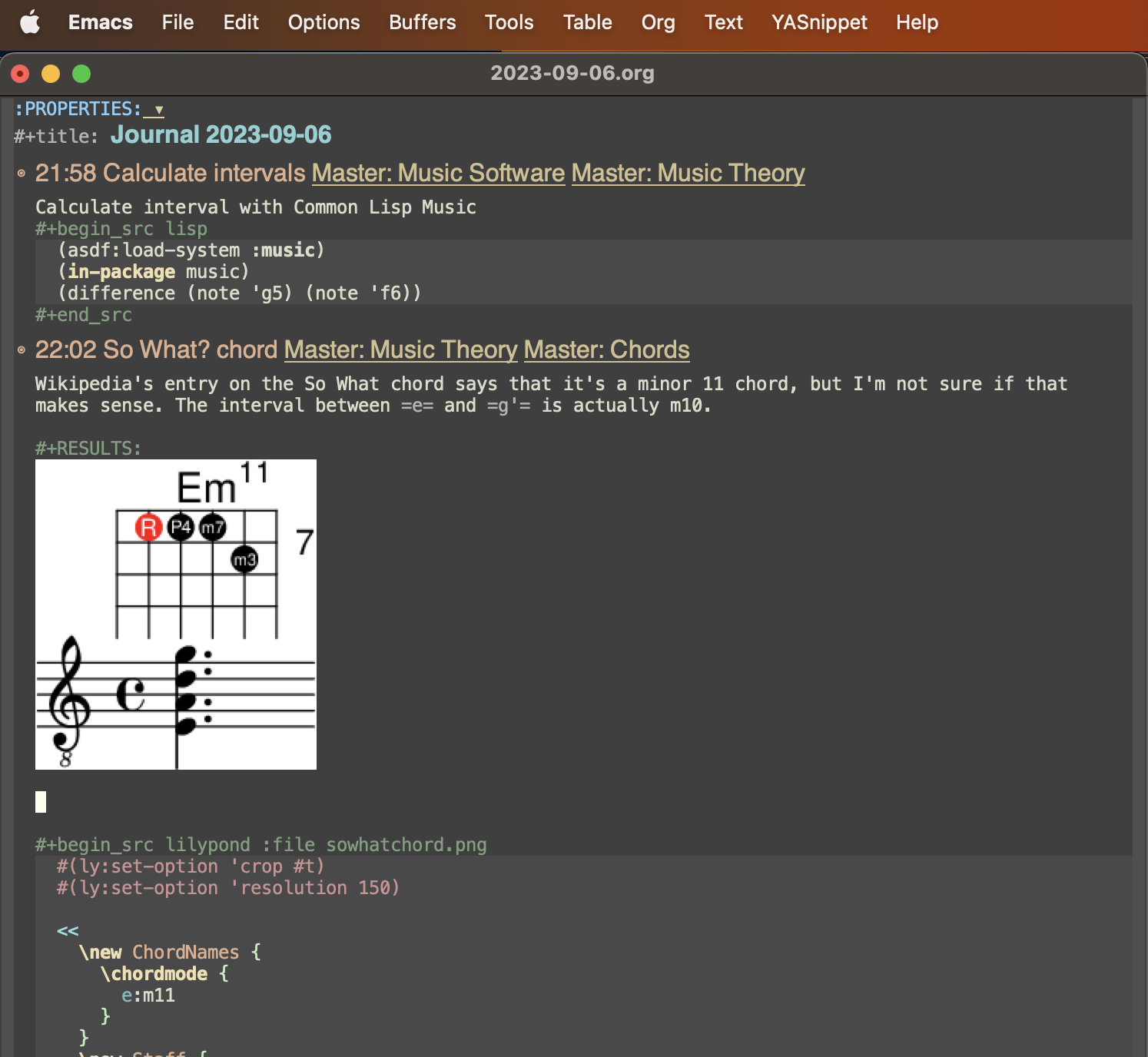

But the point of this exercise is not to just to create diagrams. What’s more important is a system to collect them and organize them. I have been using Emacs' org-roam package as a repository of my notes. Since org-roam’s own markup language allows code blocks to be embedded and executed in its documents, I can easily incorporate scale and chord diagrams into my notes. This way, they can be commented on, can be searched, and can be associated with notes using tags. The following, for example, is a journal entry:

The ability to execute code in free-form texts is enormously powerful, allowing us to integrate any kind of information with texts. That’s why markup languages are so interesting to me.

(A side note: In my setup, the Lilypond codeblock actually produced a full page image. The #(ly:set-option 'crop #t) that I put in the first line asks LilyPond to crop the image, but it the cropped image has a different filename. The filename returned by the codeblock is still the full size image. I wrote some elisp code to automatically replace the returned filename with the filename of the cropped image. However, it was not really necessary. I realized that I just have to manually edit the filename. I don’t produce many LilyPond diagrams so it’s not a real problem.)

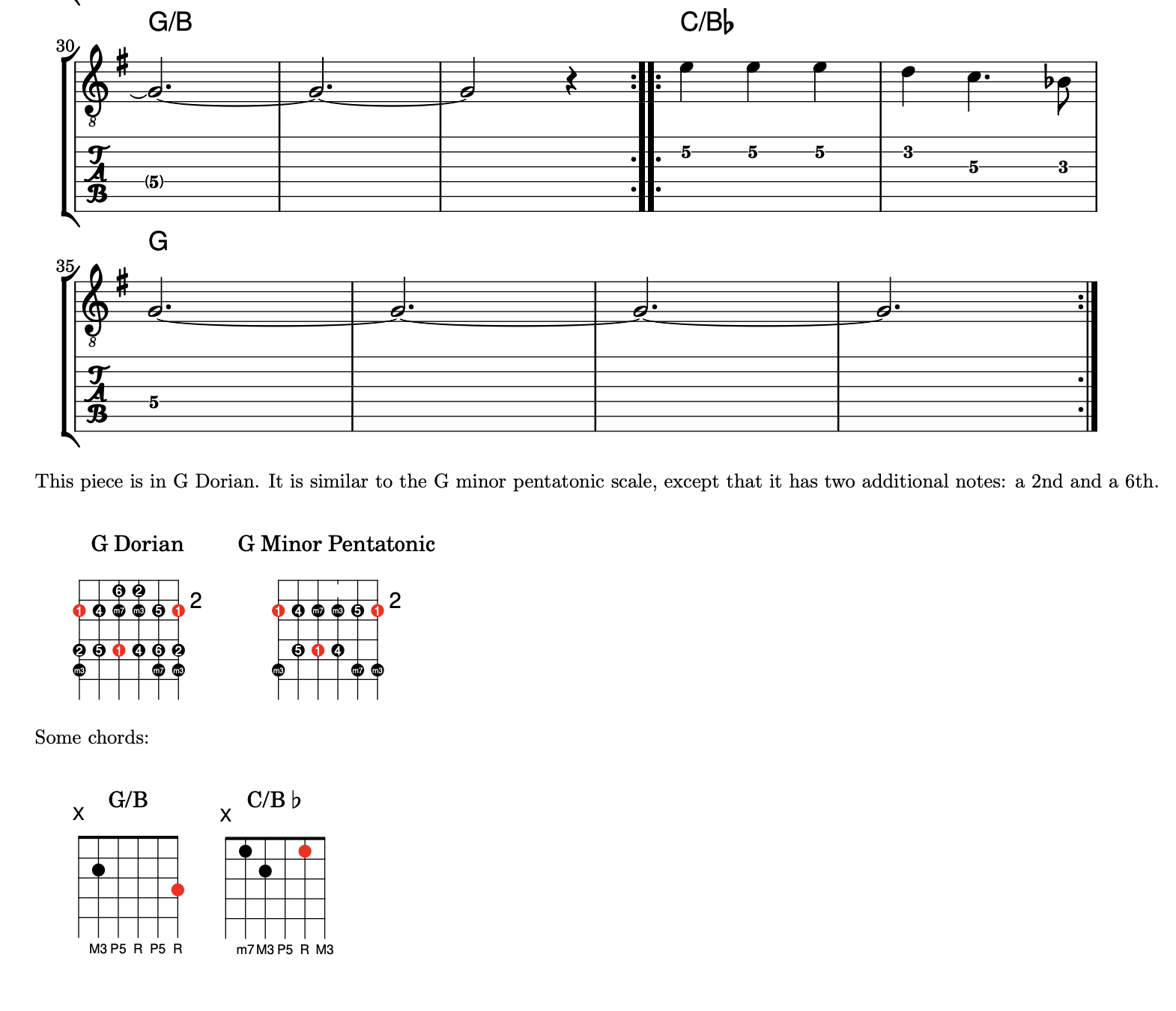

LilyPond with LaTeX

See? I don’t like just one form of information by itself. I am naturally multimodal. So after I used LilyPond to typeset a guitar tab (Bill Frisell’s Monroe; see here for the LilyPond code for the tab), I wanted to add some notes and diagrams to the tab. Luckily, it’s very easy to embed LilyPond code in yet another markup language, LaTeX! I think that’s enough markup languages for one post.